The majority of people in rural Africa and a large proportion in its urban areas rely on groundwater for drinking, hygiene, and development. The rate at which groundwater is replenished is often unknown, however, making regional water security difficult to assess.

Now, for the first time, a study showing the continent’s groundwater recharge rates may help policymakers decide how much water can be drawn from aquifers without causing substantial depletion and impact on the environment.

“Groundwater recharge is like your monthly or annual income.”

“Groundwater recharge is like your monthly or annual income,” said Alan MacDonald, a hydrogeologist with the British Geological Survey who led the study. “It determines the amount of water that you can draw from your bank. If you draw more than your income, you draw from your savings.”

With an international team from France, Nigeria, South Africa, the United Kingdom, and the United States, MacDonald examined more than 300 different studies from 1970 to 2019 and developed a data set of 134 existing recharge studies for Africa to create an overview of recharge patterns across the entire continent.

“This effort brought together extensive African knowledge with expertise from other countries to provide information to sustainably develop water resources and overcome some of the most pressing issues countries often face, such as drought, deprivation, and starvation,” said Seifu Kebede Gurmessa, a hydrologist from the University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa, and a study coauthor.

“We estimate that the long-term groundwater recharge in Africa is approximately 15,000 cubic kilometers per decade and that recharge can occur even in arid and semiarid areas,” said MacDonald. “This is equivalent to more than half the annual rainfall in Africa, which is replenishing the groundwater every decade.”

So although long-term average rainfall generally predicts groundwater recharge, the new study uncovers distinctions at local scales due to differences in land cover. It also reveals year-to-year differences associated with variability in the intensity of rainfall. The study was published in Environmental Research Letters in February.

High Storage or High Recharge—Rarely Both

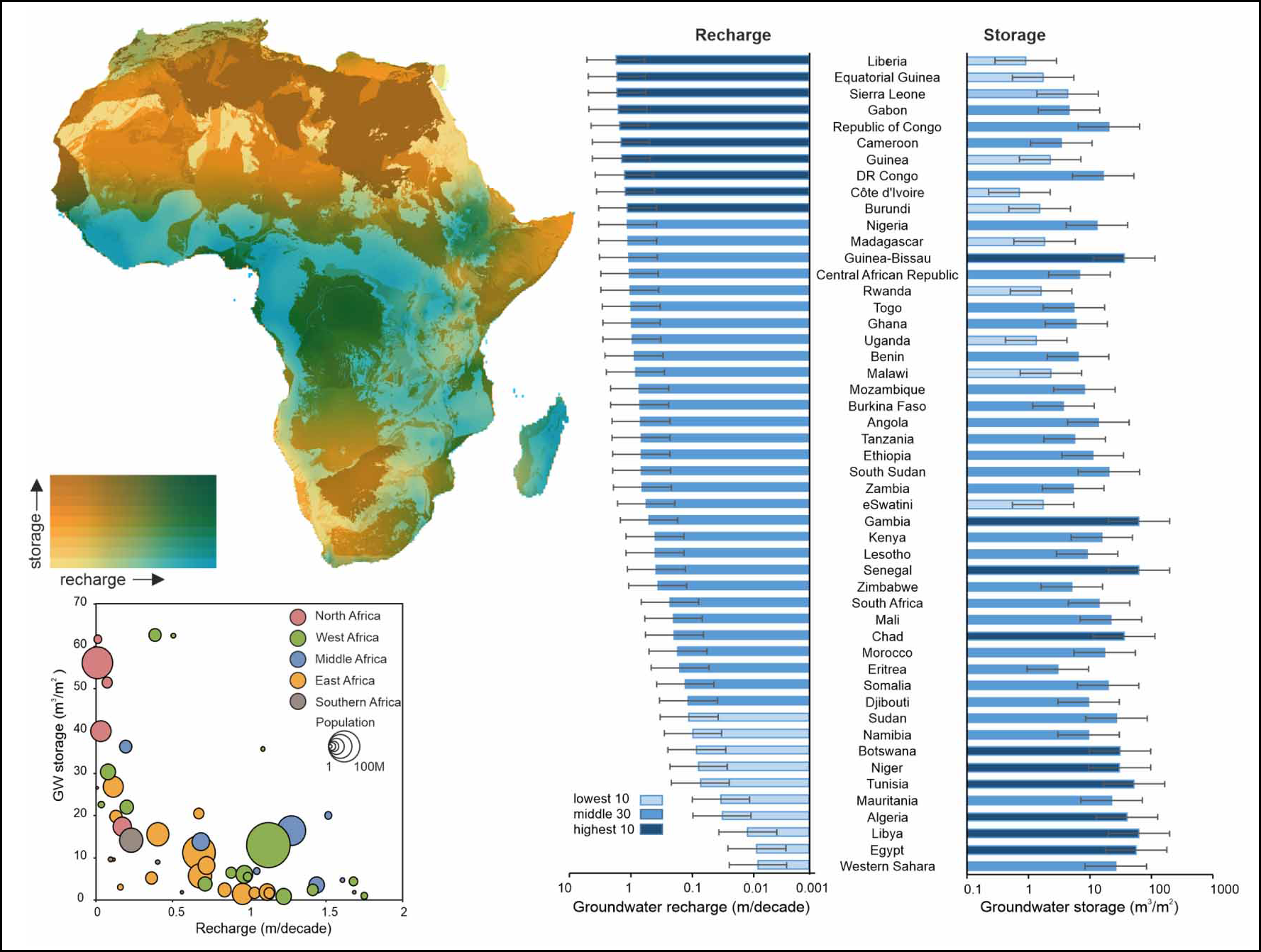

The new maps show that the majority of African countries have either high groundwater storage or high groundwater recharge—rarely both and rarely neither.

North African countries with little rainfall, including Algeria, Egypt, and Libya, have considerable groundwater storage but very low recharge rates. These regions are generally resistant to short-term drought but vulnerable to long-term depletion of groundwater resources. “In these areas, we can see the groundwater is not connected to current climate and that groundwater pumping slowly depletes a finite reserve,” MacDonald said.

African countries with smaller groundwater storage capacity but heavier rainfall and a more reliable recharge rate include Burundi, Côte d’Ivoire, and Liberia. These regions are more vulnerable to drought but more resilient to long-term depletion.

Of the 50 African countries studied, five have both groundwater storage and recharge rates above the African average: Angola, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Guinea-Bissau, Nigeria, and the Republic of the Congo. These nations are generally considered water secure.

Five of the countries studied have storage and recharge rates below the African average: Eritrea, Eswatini, Lesotho, Zambia, and Zimbabwe. These nations are often water insecure and vulnerable to short-term climate hazards and long-term depletion. Extra care is needed to monitor and develop their groundwater resources, the study authors said.

Calculating Groundwater Recharge

Estimating groundwater recharge is difficult. An aquifer’s storage capacity, regional annual rainfall, and extraction patterns all influence the calculation.

Arnaud Sterckx, a researcher at the International Groundwater Resources Assessment Centre in the Netherlands, explained that estimating groundwater recharge is difficult.

MacDonald said his team estimated recharge from multiple data sets, including long-term variations in groundwater level measured in aquifers, the concentrations of modern gases found in groundwater, ratios of different water isotopes, and the differences in chloride concentrations between rainfall and groundwater. The researchers also had to find a method to scale up the individual studies to provide maps that were useful for all of Africa.

“The authors of this study have been cautious, and they kept only the most reliable estimates available in Africa,” Sterckx said.

Considering the uncertainty inherent in the measurement, the results of this study are meant not to directly guide local or national applications but to provide an interesting picture of how resilient groundwater resources are across the continent, Sterckx said.

Eelco Lukas, director of the Institute for Groundwater Studies, University of the Free State, South Africa, agreed that although the creation of a recharge map for the whole of Africa has merit when it comes to the availability of groundwater, “the recharge is not uniform for the whole of each country, as it is highly dependent on the rainfall amount and intensity and on the geology.” Lukas was not involved in the new study.

Next Steps

“This study calls for more local-scale studies of groundwater recharge, and it calls for decision-makers at all levels to adopt appropriate groundwater management measures in line with the storage versus recharge properties of aquifers,” Sterckx said.

For MacDonald, the study provides a useful quantification of what researchers think long-term average groundwater recharge is. However, he admitted, it doesn’t tell much about the reasons for high and low recharge, particularly at a catchment scale. To answer such questions, he said several studies are now looking at “what local factors affect groundwater recharge—for example, forest cover and agricultural practice.”

—Munyaradzi Makoni (@MunyaWaMakoni), Science Writer

Citation:

Makoni, M. (2021), Scientists map Africa’s groundwater recharge for the first time, Eos, 102, https://doi.org/10.1029/2021EO156691. Published on 01 April 2021.

Text © 2021. The authors. CC BY-NC-ND 3.0

Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.